Originally published in Inqaba ya Basebenzi No. 1 (January 1981).

by Ken Mark

The strikes which have swept through South Africa in 1980 have shown that the black workers are determined to put an end to their crushing oppression by the bosses and their state. Never has it been clearer that the working class itself, in its struggle for life and freedom, will be the decisive force to topple the racist capitalist state.

The year opened with running strikes at the Ford Cortina factory in Port Elizabeth. Action followed in the huge Frametex mill in Pinetown. Strikes broke out in Port Elizabeth-Uitenhage, paralysing these towns. The big battle of the municipal workers in Johannesburg brought the workers’ struggle into the streets of the largest city of Southern Africa.

Side by side with these massive struggles, the workers in the smaller plants such as the Fattis and Monis factory and the meat industry in Cape Town, have shown their determination to fight for weeks and even months for their demands.

Including the Cape stay-at-home on 16 June, hundreds of thousands of workers have been involved. Throughout the country the workers’ spirit has been held high by the disciplined mass struggle of the strikers and by the victories which have been won.

The workers in South Africa are no strangers to the strike weapon. What has made the strike movement of 1980 so important to the struggle to end apartheid and the rule of the bosses?

National Movement

The events of the past months show that enormous advances have been made by the black workers. As the capitalists become more confused about the way forward, and manoeuvres like the ‘President’s Council’ are exposed to the ridicule of the masses, the workers’ movement is growing in strength and determination.

We are witnessing the unprecedented development of strike action on a national scale as the actions in one area spark off those in another: in Port Elizabeth, Cape Town, Durban, again Port Elizabeth and Uitenhage, Johannesburg and East London. These strikes bring back memories of the Natal strikes of 1973 and the political strikes of 1976. But the workers’ movement reaches further ahead with each assault – grasping the future with both hands.

Political Demands

While there have been setbacks in the Cape Town meat strike and the Johannesburg municipal strike, the workers’ movement stands unbowed. The strike wave sweeps up the beach of reaction, retreats for a moment, but then pounds again forward with renewed vigour. Nowhere has this been better shown than in the municipal strike. Although the vicious municipal bureaucrats and the police thought they had broken the workers’ spirit by crushing the strike with force of arms, the strikers remain loyal to the Black Municipal Workers’ Union and the workers still continue to join up in large numbers. There is none of the back-biting and confusion as on the side of the bosses.

The advance of the workers’ movement is clear from the increasingly political demands being made.

As in Brazil and many other capitalist countries – and now also in Poland – the demand for free trade union organisation and the right to strike raises the trade union question itself into a major political issue.

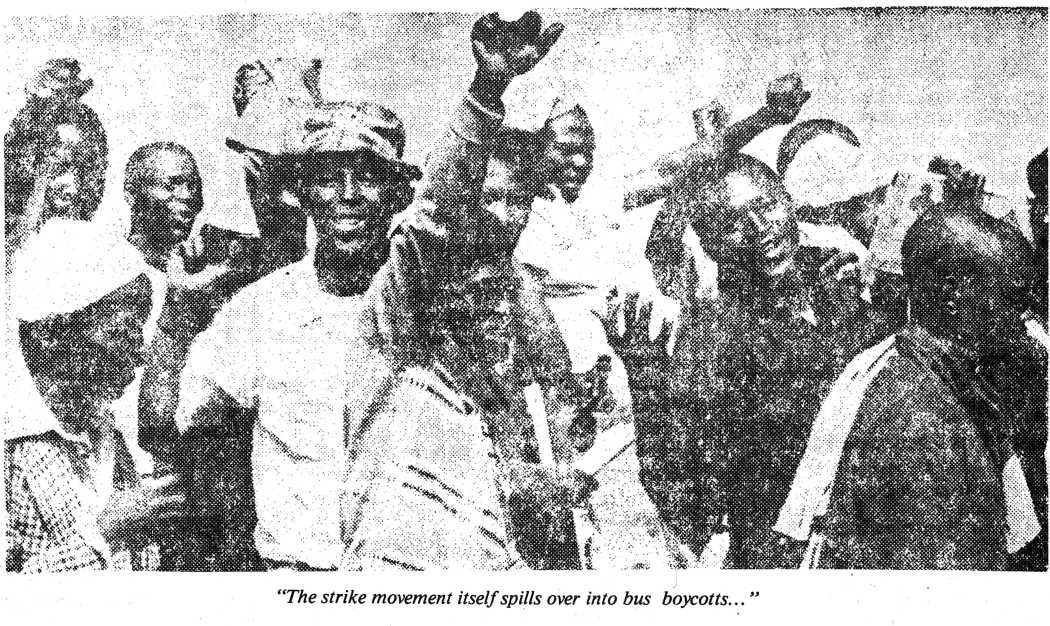

The regime is forced to change its laws to accept the living reality of the workers’ organisation. But strikers have taken the issues further. The strike movement itself spills over into bus boycotts (as in Cape Town) and rent strikes (as in Soweto).The workers are connecting the township and factory struggles, working through many political organisations of the oppressed (as in Port Elizabeth), and demanding the right to free meetings.

These developments point to the increasingly organised nature of the strike movement. Most of the strikes now taking place are in factories where the unions have been active. When strikes break out, increasingly strike committees are set up to build financial and political support. Steeled workers’ leaders arise continually from the rank-and-file.

The municipal strike showed the extent to which disunity between migrant and non-migrant workers can be healed in the forward march of the struggle.

But, more than ever, it has become clear that the workers can only be united in the compounds and townships through organisation. In the municipal strike it was the members of the Black Municipal Workers’ Union themselves – particularly the transport workers – who carried the information between the compounds and places of work and acted as union organisers.

The enormous strength of this strike came from this unity of migrant and non-migrant workers. The compounds were transformed into strongholds of the workers’ movement. It was the rank-and-file, mainly migrants, who insisted on the need to back-up the demand for an increase in weekly wages from R35 to R58 with strike action.

Some in the union leadership argued for the union to be registered and for negotiations to begin. But it is important to be clear on this issue: the unity of migrant and non-migrant workers cannot be achieved through registration with a regime which regards blacks as foreigners.

Despite the courage and determination of the migrant workers – present also in the Fattis and Monis strike, the meat strike, and elsewhere – the leadership of some of the open trade unions has not given this question of unity enough serious attention.

Bold Demands

Fearful of the explosive force of the workers united and organised, reformist trade union leaders shrink from the bold wage demands and attack those unions refusing to register. Despite this discouragement the workers hold to these demands with a firm grip. Increasingly the reformist leaders look isolated and out of temper with the strike movement, as in the Eastern Cape motor industry.

All trade union leadership which refuses to give priority to the organisation of the mass of the black workers – the migrant workers – will be operating as a brake on the struggle against the bosses’ system.

As a result of the indifference and even hostility of the leaders of the registered unions, and the reformist and corrupt leadership of some open and parallel unions, the workers on strike often turn to the community organisations in the townships.

The workers’ expectations of assistance from the community organisations in the townships are increased by the unity of the oppressed created in the struggle against apartheid, especially against racist education and the stooges in the ‘community councils’.

Faced by the powerful strike movement the middle class leadership in the community organisations is pulled in the direction of the workers and supports many of the demands of the workers. But until the working class develops its own political organisation to unite the workers in the factory and township, the middle class will make claims on the workers’ behalf only to retreat again when compromises are at hand.

Solidarity

Up to now community support has mainly taken the form of consumer boycotts and money collected for strikers. It has been shown most clearly in the boycott movement around Fattis and Monis products and meat in Cape Town. Such support has been useful, but the strength of the workers arises through unity and organisation at the point of production.

The boycott of spaghetti, meat, and now furniture, can develop as consumer campaigns because these things are within the reach of many blacks. But consumer action cannot stop the flow of heavy steel or gold.

The boycott campaigns have added weight to the support of the workers’ movement, but they cannot take the place of national action by organised workers in support of each other’s struggles.

Support from the churches and liberals can only be a temporary phase in the struggle. As the workers’ demands sharpen politically this money will dry up.

To sustain strikers’ families, unregistered unions can raise support for each other through donations by members and collections in the townships. This money must be held under the full control of the workers’ committees with regular reports to mass meetings.

Support Committees

Strikes can be supported by workers in other factories refusing to handle products of factories on strike. In this way, the workers can bring colossal pressure to bear on the employers. Post can be halted to factories on strike, no goods delivered or taken out by transport workers, and even the electricity cut-off. As workers rally to the support of a particular struggle the basis is laid for general strike action.

Effective organisation is needed to develop the struggle to this level. As a means to this end, strike support committees should be considered by workers involved in the struggles, to be made-up of representatives from all the local trade unions and factories in the area.

Where trade union leaders refuse to participate, the demand for support should be taken to the rank-and-file, shop stewards and branches. Reformist leaders can be decisively exposed when they refuse to support other workers in struggle.

The workers’ movement must advance with all speed to create a popular trade union press to support and spread its case. We must not be dependent on putting our case through the bosses’ press.

The establishment of national federations and the amalgamation of unions express the strivings for unity in the workers’ movement. Yet unified national and even regional trade union organisation is still fragile. A major task of the next period is to bring into existence a single trade union federation, uniting migrant and non-migrant workers in their millions under one umbrella. Among leaders of the existing trade unions, shop stewards, and in all factories whether unionised or not, discussion should take place to work out how to bring this about. A key issue to be taken up is how a national conference of delegates from the workplaces could be convened to resolve the question of trade union unity.

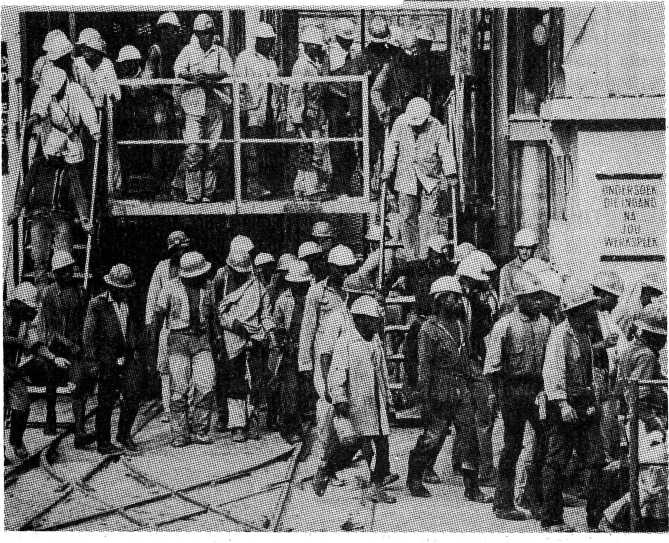

The strike movement has proved to all who had to be convinced that the ‘new dispensation in labour relations’ promised by Professor Wiehahn is simply a new version of the old recipe of control and repression. The regime has declared open warfare on the strike leaders. In Pinetown, Samson Cele, a textile strike leader awaiting trial, was murdered. Other leaders have been arrested and tortured.

The Johannesburg municipal strikers were removed from the city at gunpoint and dumped in the Bantustans. Leaders of the Black Municipal Workers’ Union have been charged with sabotage and faced a possible death sentence.

United Action

Nothing other than the united action of the workers can hold the regime back from measures of this kind. The strike movement thus forms part and parcel of the political struggle for national and social liberation. The struggle for revolutionary leadership in the trade unions cannot be separated from the development of underground political leadership and a socialist programme as the guideline for trade union as well as political struggle. Throughout the land the workers should be fighting for the growth of the African National Congress as an organisation led by the working class on the basis of Marxist policies.

The question of programme is vital since the workers’ demands can only be met with an end, not only to the apartheid regime, but also to the system of capitalism which it defends. The bosses are united in denouncing the workers’ present demands for wages double or even three times the existing level, as a threat to the profit system which keeps them in power.

Against the workers’ movement the regime has tightened the pass system and threatens to outlaw those unions refusing to register. The big capitalists say frankly that real reforms are not possible under capitalism. Etheredge of the Anglo-American Corporation said recently that the mines were committed to migrant labour even if apartheid was abolished!

While the regime can threaten the African governments with the atom bomb and undertake military invasions of the ‘front line states’, in the last few months it has been forced to admit that the industrial areas of South Africa, the very basis for its military strength, are the real ‘operational zones’.

More blows have been rained on the ruling class by the mass of the workers in action in the space of one year than in twenty years of guerrilla operations. The social power of the working class is greater than the military power of the state.

The movement of the working class itself has thrown the ruling class into confusion as the old basis of its rule begins to crumble. Already in the case of the militant strike action by the black municipal workers, some white workers (relied on by the regime), stood to one side rather than risk themselves in scabbing.

The workers movement offers the prospect of overthrowing the apartheid regime in the nerve centres of its power, and the construction of a democratic socialist order in South Africa. 1980 has shown how the strike movement can serve as a rallying point in this struggle and a school of learning for making clear the revolutionary tasks which the working class alone has the power to undertake.

The workers have shown the way forward. Through strike action they have turned the city streets, the factories, harbours, and mines, into the arena of combat for workers’ rule in South Africa.

© Transcribed from the original by the Marxist Workers Party (2021).