Originally appeared in Inqaba ya Basebenzi No. 20/21 (September 1986).

“A Thousand ways to die” is the title of a safety manual just produced by the NUM. Even before it was released, its message was horribly underlined by the disaster at Gencor’s Kinross gold-mine on 16 September, in which 177 mineworkers died.

The disaster highlights the callous lack of concern of the profit-grabbing mine bosses for workers’ safety. As NUM General Secretary Cyril Ramaphosa said, it was “completely unnecessary”.

A welding accident 1.6 kilometers underground started a fire – but there was no fire extinguisher to hand. The fire set alight polyurethane foam lining the tunnel – material known for more than 20 years to be a deadly hazard in mines and banned in, for example, Britain. It was the toxic fumes unleashed, and fanned 1.5 kilometres along the tunnel by the ventilation system, which caused all the deaths.

Gencor are guilty of murder, and must be held responsible.

Workers everywhere will endorse the NUM’s decision for a one-day strike on 1 October in protest.

The 100-year history of the SA mining industry is written in blood and sweat – of black workers slaving at starvation wages, separated from their families in overcrowded hostels, forced to gamble with their lives.

Since the turn of the century, over 48,000 workers have died in the gold-mines alone.

The Chamber of Mines churns out propaganda on how its safety record “is second to none”, and this is barely challenged by the capitalist media in SA and abroad. Yet the fatality and accident rate in SA mines is several times that in Britain or the United States.

Between 1978 and 1983 the death rate on UK coal mines was 0.1 per 1,000 miners; and in the US less than 1 per 1,000. Chamber of Mines reports analysed by researcher Jean Leger show a death rate of 2 per 1,000 in 1978 and 1.62 per 1,000 in 1984 – no better than the rate of 1.96 per 1,000 in 1941.

Moreover, while in the US an accident becomes ‘reportable’ if it prevents the miner from working the next shift, and in the UK if it prevents him from working more than three days, in SA it is ‘reportable’ only if it prevents the mineworker from returning to work within fourteen days.

The system of paying white miners’ productivity bonuses is also an incentive for them to cut corners on safety.

Reactionary white miners’ leader’ Arrie Paulus agrees with the activists in SA Chamber on the safeness of the mines. This will be small comfort to the colleagues and families of the five white miners who died. White miners should turn instead to the SA NUM – not, of course, in any hope of defending their past privileges, but for a way forward as miners together.

With the rand falling and the gold-price rising, mine bosses have been making record profits: R1,900 million (£600 million) in 1985, and more this year. Gencor’s R458 million (£143 million) share in 1985 was up 56% on the previous year. Yet less than 2% of the Chamber’s R40 million a year research budget is spent on safety research.

The mine bosses refuse to reinvest in adequate safety measures – and also stand fiercely against black mineworkers’ demands for a living wage.

This year they have conceded a 17-21% increase (with inflation touching 20%), and may increase this fractionally in the negotiations still to be concluded. This was in response to the NUM’s original demand of 40%, which is the level of increase that is required even to begin to lift the burden of poverty wages.

Miserly

It is also these wage levels – R193 a month the starting rate on the gold-mines, and R177 on the coal mines – which will provide the basis for the miserly ‘compensation’ payments in the disaster: two years’ wages lump-sum and 75% of wages thereafter to dependants.

The NUM is campaigning for a Bill of Rights on safety, including the right to refuse dangerous work, to have access to management safety records, proper training, and worker representation on safety committees.

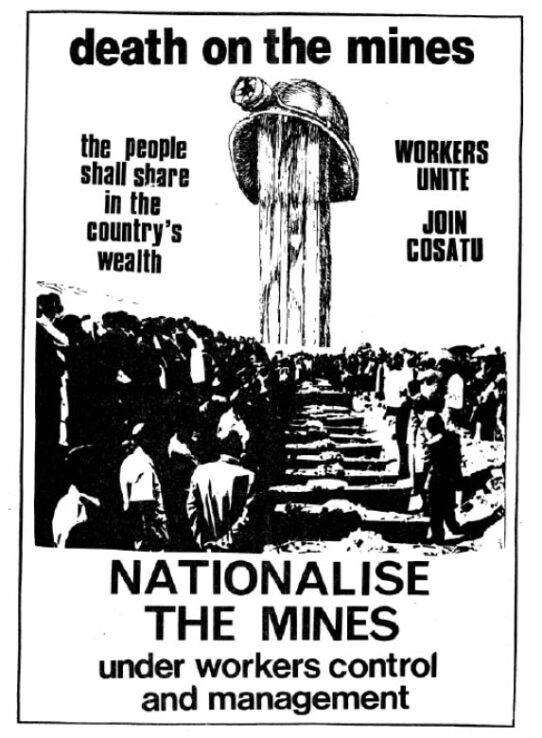

Acceptance of these by the mine bosses would be a step forward. But, as SA NUM policy affirms, poverty, migrant labour, and unsafe conditions can be ended for mineworkers only when the mines are nationalised under workers’ control and management.

Even then, gold – unlike coal – is “useful” mainly as a store of wealth for capitalists and their governments. The risk inherent in deep-level gold-mining can be ended finally only through socialism worldwide – when gold’s use will, in Lenin’s words, become limited to ‘decorating public lavatories’ and goldminers can be redeployed in safe jobs.

Now, however, for SA mineworkers and their comrades internationally, it is the time to show anger, and determination to carry forward the struggle for safety and for an end to the chains of apartheid and capitalism that enslave them.

© Transcribed from the original by the Marxist Workers Party (2021).