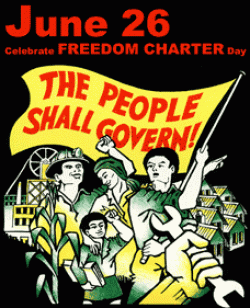

Blueprint for socialism or capitalism?

One year ahead of the 70th anniversary of the congress of the people, the political landscape has been changed decisively by the outcome of the 29th May elections. The party that made the freedom charter its manifesto for the mobilisation of the masses, lost its majority for the first time since it came into power in 1994.Many say that the ANC suffered this defeat because it had abandoned the freedom charter and adopted the neo-liberal GEAR programme in 1996 in its place. Discussions about the way forward for the working class, the question of the worker’s party and what programme that party should be based on are taking place afresh. We republish this article first released in 2015 and republished in 2019, as a contribution to the debate about the way forward for the working class and in support for the establishment of a mass worker’s party on a socialist programme.

This is an edited version of an article originally published in 2015 to intervene in debates taking place within the workers movement about the relevance of the Freedom Charter.

by Weizmann Hamilton, 2015

The ANC has always portrayed itself as a multi-class party with the leadership insisting that, whilst it was biased towards the poor, it represents equally the interests of all South Africans, rich and poor, white and black, workers, professionals, petty bourgeois, capitalists, liberals, democrats and revolutionaries. The composition of the [1955] Congress of the People [held in Kliptown] reflected this. In fact, astonishingly, even the Nationalist Party, oppressors of the people and architects of the recently introduced apartheid system, was invited but declined to attend. The NP preferred not to participate in a charade of political “happy families” concentrating its efforts instead on the more serious business of trying to sabotage the Congress. The Congress was a convention of conflicting class interests and competing ideologies with no prospect of it emerging with a Charter that spoke unambiguously in the name of the working class.

Thus the Charter included nationalisation clauses but not a word either about capitalism or socialism. The leadership genuinely believed for a long period that nationalisation was essential if the aspirant black capitalist class was to take control of the commanding heights of the economy. Its vision was of a capitalist economy in which the black capitalist class would occupy at its summits a position corresponding to the weight of the black population in society. Freedom for the aspirant black capitalist class meant a predominantly black capitalist class instead of one dominated by a white minority.

The contradictions in the contributions, and the fierce debates that raged at the Congress were rooted in the opposing class positions from which the worker delegates and the capitalist delegates approached the nature and tasks of the struggle.

How worker delegates saw the Charter

The Congress of the People provided the first opportunity for testing the balance of power in the relationship between the black working class and the petty bourgeois leadership of the ANC since the ANC had turned to the masses for support in the struggle against apartheid. Despite the common opposition to apartheid, the process of drafting the Charter revealed the conflicting aspirations of the different classes at the congress. ANC leader Ben Turok, who was responsible for drafting the economic clauses, confirms that the process was controversial with many delegates feeling that the Charter was not radical enough.

Although the word “socialism” does not appear anywhere in the Charter, records of the proceedings show that the interpretation of the economic clauses by the working class delegates was in direct contradiction to Mandela’s. As the Marxist Workers Tendency of the ANC – predecessors to the Democratic Socialist Movement and co-founders of WASP – pointed out in its 1982 publication SA’s Impending Socialist Revolution, the mover of the clause: “The people shall share in the country’s wealth” explained it to the delegates as follows:

“It [the Charter] says the ownership of the mines will be transferred to the people. It says wherever there is a gold mine there will no longer be a compound boss. There will be a committee of the workers to run the mine. …wherever there is a factory and … workers are exploited, we say that that the workers will take over and run the factories. In other words, the ownership of the factories will come into the hands of the people. … Let the banks come back to the people, let us have a people’s committee to run the banks.”

The next speaker, representing trade unions in Natal, spelled out with complete clarity the meaning the workers attached to the clause:

“Now comrades, the biggest difficult we are facing in South Africa is that one of capitalism in all its oppressive measures versus the ordinary people – the ordinary workers in the country. We find in this country, as the mover of the resolution pointed out, the means of production. The factories, the lands, the industries and everything possible is owned by a small group of people who are the capitalists in this country. They skin the people, they live on the fat of the workers and make them work, as a matter of fact in exploitation. …this is a very important demand in the Freedom Charter. Now we would like to see a South Africa where the industries, the land, the big business and the mines, and everything that is owned by a small group of people in this country must be owned by all the people in this country. That is what we demand, this is what we fight for and until we have achieved it, we must not rest.”

The vague contradictory nature of the formulations in the Charter reflected the success of the capitalist leadership in diluting the more radical socialist aspirations of the workers. From the standpoint of the worker delegates, the most important conquest was the nationalisation clause. In spite of the fact that the Charter does not call specifically for the abolition of capitalism, the sweeping nationalisation the Charter calls for at least poses the question of the abolition even if it does not answer it. The omission of the word socialism is not accidental, it reflects the dominance of the capitalist delegates at the Congress.

How the capitalists saw the Charter

Building on their success in purging the Charter of the revolutionary strivings of the workers, the leadership was at pains, throughout the entire period after the adoption of the Charter up to the end of apartheid and beyond, to clarify what they understood the Charter to stand for. The most striking of these “clarifications” was given by Mandela himself in an article In our Life Time published in Liberation in June 1956.

“Whilst the Charter proclaims democratic changes of a far-reaching nature it is by no means a blueprint for a socialist state but a programme for the unification of various classes and groupings amongst the people on a democratic basis. Under socialism the workers hold state power. They and the peasants own the means of production, the land the factories and the mills. All production is for use and not for profit. The Charter does not contemplate such profound political and economic changes. Its declaration “The People Shall Govern!” visualises the transfer of power not to any single social class but to all the people of this country be they workers, peasants, professional men or petty bourgeoisie. (emphasis added)

“It is true that in demanding the nationalisation of the banks, the mines and the land, the Charter strikes a fatal blow at the financial and gold mining monopolies and farming interests that have for centuries plundered the country and condemned it people to servitude. But such a step absolutely imperative and necessary because the realisation of the Charter is inconceivable, in fact impossible, unless and until these monopolies are first smashed up and the national wealth of the country turned over to the people.

“The breaking up and democratisation of these monopolies will open up fresh fields for the development of a prosperous non-European bourgeois class. For the first time in the history of this country the non-European bourgeoisie will have the opportunity to own, in their own name and right, mines and factories, and trade and private enterprise will boom and flourish as never before.” (emphasis added)

Of all the repeated “clarifications” by the ANC leadership, Mandela’s is the clearest declaration of the separate and in fact opposing class interests of the black working class and that of the aspirant bourgeoisie the ANC was founded to represent. What is spelled out in this article is that the leadership had no quarrel with “free enterprise”, that is capitalism. Their objection was that the black bourgeoisie had been denied the opportunity to occupy the same position as white monopoly capital at the summits of the economy. The presentation of what were in fact the separate and distinct aspirations of the black bourgeoisie as those of “all the social classes” is a deception that the bourgeoisie everywhere has been obliged to resort to throughout its history.

The idea that all social classes own equally the commanding heights of the economy under capitalism is a complete falsehood. But the bourgeoisie is obliged to present the relationship between the classes in this manner because, as a tiny minority in society, they can fulfil their aspirations only by marshalling the support of the “people”, that is the working class masses who alone have the capacity to shake the old order. This deceit is not unique to SA. It is the method not only of the colonial bourgeoisie but in fact of the bourgeois even during the rise of capitalism.

The Charter’s shortcomings

The Charter has obvious shortcomings. It does not provide for the right to strike. There are no demands for the eradication of the oppression of and discrimination against women, LGBTQ people, nor any on the environment, demands that have risen to the top of the working class agenda today. But these shortcomings can be easily remedied. This would make the Freedom Charter even more radical. In fact its demands are already so radical that it is impossible for all of them to be implemented within the framework of capitalism. The full implementation of the Charter requires the overthrow of capitalism and the socialist transformation of society.

The Charter’s most serious shortcoming, however, lies not so much in these omissions, but in the fact that it is completely silent on the fact that its demands are incompatible with capitalism. The Charter fails to spell out what measures would have to be taken to enable the working class to carry out the expropriation of the capitalist class and to create basis for its own rule. The Charter also does not explain that the nationalisation of the commanding heights of the economy is the only means by which a future government would be able to place the resources in its hands to enable it to fulfil all the other demands like free education and health and to substitute the anarchy of the free market with a democratically planned economy. Radical as the demand for the nationalisation of the commanding heights of the economy are, the Charter omits to qualify the nationalisation demand by linking it to workers control and management.

Nationalisation and Socialism

What the worker delegates to the Congress expressed could be realised only through the overthrow of capitalism even if that was not stated explicitly. It is therefore entirely incorrect to argue as is done in the 60th Anniversary of the Freedom Charter publication produced by Workers World Media (WWM) that the adoption of the nationalisation clauses was of little significance as the idea of nationalisation was widely accepted at the time. It may be true that following the Second World War many capitalist governments in the West implemented nationalisation to such an extent that as much as 60% of the world’s economy was under state control at one time in that period as WWM points out. But these capitalist governments acted under the pressure of a massive post-war movement of the working class, and given the economic crisis and the radicalisation of the working class were compelled to take measures to contain the movement – to make concessions from above to stop revolution from below.

To dismiss the nationalisation clauses of the Charter as if the delegates were merely dressing themselves up in the latest policy fashion garments, is to dismiss the outlook of the worker delegates. It also tears the Congress from the historical context of the political situation prevailing in SA at the time.

The Congress of the People occurred against the background of the biggest mass movement of the black oppressed since the colonisation of the country and was itself the largest democratic gathering ever. What the worker delegates showed at that time already was the understanding that the struggle for national liberation was bound up inextricably with the struggle against capitalism. The outlook of the workers delegates could only mean in practice that the attainment of the demand for national liberation and democracy would require the method of class struggle against the capitalist class whose exploitation of their labour in the workplace was enforced and protected by the same white minority regime that held them in subjugation as blacks through apartheid.

The revolution the workers had in mind could therefore not stop once white minority rule and apartheid had been overthrown but would pass on uninterruptedly to the overthrow of capitalism as well. This is the meaning of the theory of permanent revolution as first explained by Marx and Engels … and elaborated by Trotsky in the context of the Russian Revolution a half-a- century later.

In this schema nationalisation was absolutely critical to the fulfilment of the aims of the revolution. That the bureaucracies in Russia (after the degeneration of revolution) China and Eastern Europe after the second world war rested on state-controlled economies does not in any way diminish the importance of nationalisation as a policy indispensable to the ability of the working class in its revolution to break the power of the capitalist class, establish its rule and proceed with the thoroughgoing transformation of society.

The SA Communist Party

The attitude that nationalisation is neither here nor there would have meant not taking the side of the worker delegates at the Congress, and turning one’s back against the entire proceedings. It would have the same effect as the actual role played by the SACP at the Congress, which, instead of bolstering the demands of the workers and filling them with revolutionary content, held the workers back, herding them like cattle behind the petty bourgeois on the basis of the National Democratic Revolution (NDR). That the SACP was unable to participate in the Congress as a party because it was banned was in fact no barrier to its participation. It had many delegates who participated as ANC members. The NDR dictated that the SACP members should participate in the ANC not to promote the interests of their party and the proletariat in whose name it spoke, but those of the capitalist leadership of the ANC. Upon entering an ANC meeting room they dutifully left the SACP hats outside. This meant in fact bolstering the right against the left at the Congress.

Any communist party worthy of the name would have used the Congress to ensure that the Freedom Charter contained clauses that made explicit what was implicit in the worker delegates’ minds ensuring the inclusion of socialist clauses. A genuine communist party would have called for the substitution of the Charter’s liberal preamble with one that places the working class at the head of the nation, and outlines a vision of society based on the transfer of the wealth of the country to the people by the nationalisation of the commanding heights of the economy under the democratic control and management of the working class. A socialist preamble would go further to explain that this would require the overthrow of capitalism, the smashing of the state and the creation of a state of workers democracy by replicating the workplace committees the worker delegates referred to by the worker delegates, in communities and cities linking them country-wide.

But imprisoned in the Stalinist two-stage theory, the SACP became the political handmaidens of the ANC bourgeois, providing them with the theoretical justification for their determination to remain firmly within the framework of capitalism and therefore, in the final analysis, collaborators of the capitalist class and imperialism.

1980s revolutionary movement

The real question that should be asked is why if, even in its most radical moment, when it had inscribed into the Charter demands for the nationalisation of the commanding heights of the economy for the purpose not of overthrowing capitalism, but deracialising it, the ANC eventually abandoned nationalisation.

The capitalist class, who are in the business of protecting their wealth, power and privilege and keeping their boots on the necks of the workers, take a far more serious attitude to the question of nationalisation than the comrades of WWM who think that it but one policy option amongst many on the supermarket shelves of capitalist rule. When as they have done under the current Great Recession, occasionally resort to nationalisation, it is only a temporary measure to rescue ailing companies at the expense of the state only to hand them back to private owners for a song as soon as possible afterwards.

It is an entirely different matter when the nationalisation demand is demanded by their class enemies, the working class. Like bloodhounds, the capitalists detected the scent of working class influence in the nationalisation clauses of the Charter, despite the camouflage of its woolly phraseology. They take account not only of who makes such demands, but also of the circumstances under which they are made.

The negotiated settlement signed at the Congress for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa) did not spring out of a clear blue sky driven by a regime and a capitalist class who had undergone a conversion on the road to Damascus along which they had discovered that black people had human rights and that democracy may not be such a bad thing after all. It was the culmination of secret talks with Mandela in prison and with selected ANC leaders abroad initiated by business, apartheid intelligence services, and representatives of the Afrikaner elite under the hot breath of the insurrectionary movement developing in SA at that time.

The 1973 Durban strikes, the countrywide revolt in 1976 detonated by the Soweto Uprising, the unity of workers and youth in the 80s, the birth of UDF in 1983, the acquisition by the mass movement of an increasingly insurrectionary character as the youth and workers moved blended into one between 1984-86, overcoming the repression of both the partial state of emergency in 1985 and the permanent one in 1986, and most decisively of all, the birth of Cosatu in 1985, concentrated minds of the bourgeoisie wonderfully. They could see the writing on the wall for white minority rule. What alarmed the strategists of the bourgeois most of all was the consciousness of the black working class.

How the capitalist evaluated the situation is revealed in the comments of the capitalist press of the time. “The two major demands of the Freedom Charter are that the ‘people shall share in the country’s wealth’ and ‘the land shall be shared among those who work it’. The fact that businessmen sought yesterday’s talks, reflects the deep concern felt by South African big business at the increasing radicalisation of black thinking and the growing rejection of the free enterprise system. What the businessmen wanted to know was the degree to which to which this view was shared by the ANC leadership. ” (Financial Times UK 14th September 1985)

A year later the same paper quoted Anglo American director Zac De Beer, one of the participants in talks with the ANC, as saying: “We all understand how years of apartheid has caused many blacks to reject the economic as well as the political system. But we dare not allow the baby of free enterprise to be thrown out with the bathwater of apartheid” (Financial Times UK 10th June, 1986).

Thus whilst hypocritically wringing their hands over the “unfortunate” measures the state had to take to restore stability through the State of Emergency, big business undertook the political Great Trek to Lusaka, Dakar, London and Washington to engage the ANC leadership. The strategic aim of these discussions was to emasculate the Freedom Charter by exerting relentless pressure on the ANC to abandon nationalisation and thereby turn the ANC into their conscious collaborators in diverting the revolution and preserving capitalism.

Whatever the intentions of the ANC leadership, were they to attempt to implement the nationalisation clauses of the Charter, what would be posed is the overthrow of capitalism itself. They would not be able to proceed in that direction in any case without the mobilisation of the masses. But since the intention of the aspirant black capitalist class is not to create a socialist society, the commanding heights of the economy shall have been taken out of the hands of white monopoly capital only to be placed in those of the black capitalist class. The working class would be expected after acting as the foot soldiers of the black bourgeoisie in the NDR, to take their place at the bottom of the social pyramid as before and to serve their new masters. That is a scenario that would have resulted either in an uprising against the ANC government or the ANC itself would have been pushed to the left.

This was far too risky for both the ANC petty bourgeois leadership as well as the ruling capitalist class. The strategist of capital understood that the ANC, in adhering to nationalisation meant no harm to capitalism – a system they had wanted to be part of from the day it was formed in 1912. The problem was that the ANC would be able to carry out the policy of nationalisation only by expropriating the capitalist class. This would not have been possible through a mere legislative process. The masses would have had to be mobilised to overcome the inevitable resistance of the capitalist class who would have resorted to armed force to protect their wealth and property.

In the context of the uprisings taking place and the radicalisation of the masses, the perspective would be one of civil war. As the flames of revolution reached higher the Financial Mail (6th December, 1985) warned:

“Interventionist military action in a last ditch attempt to retain the status quo… has not been discounted in some quarters. Just which would be the worst case scenario – a dictatorship of the Left or of the Right – is open to conjecture. Few, however, who have any insight into the ideological drift of the African National Congress Freedom Charter and its talk of nationalisation, have any serious doubts on that score. Anything would be preferable to seeing SA’s economy decimated by such crude attempts at ‘wealth redistribution’ implicit in the doctrine of the Charter.”

The bourgeois would have had no hesitation to try and drown the revolution in blood. But that was not the preferred first option of the bourgeois. Given the racial balance of forces, and the temper of the masses who, far from being cowed by the State of Emergency reacted to it as to the whip of the counter-revolution, intensifying the struggle, a military solution was too risky. Its outcome was not at all a certainty, could spark racial civil war and inevitably lead to SA’s further isolation internationally.

The only way in which the ANC would then be able to carry through nationalisation would be by the mobilisation of the working class, an armed insurrection and the seizure of power by force. Uncertain of the outcome of such a scenario, the bourgeois concentrated on ensnaring the ANC leadership in a negotiated surrender, secure in the knowledge that if the ANC leadership faced a choice between leading a socialist revolution and collaborating with them, the ANC would choose the latter.

The strategist of capital thus set about the task of co-opting the ANC, ensnaring it in negotiations that culminated in the betrayal at Codesa. In a massive propaganda campaign negotiated settlement was presented as a “miracle” by the media in SA and internationally and as a “democratic breakthrough” by the SACP.

ANC capitulates

This pressure paid off handsomely. The leadership went into headlong retreat with the SACP providing the theoretical cover for this cowardly capitulation. By October of that year ANC president Oliver Tambo gave British imperialism the assurance in an address to the Foreign Affairs Committee in the House of Commons of the British parliament that the Freedom Charter “does not even purport to destroy the capitalist system.” Earlier that month Zac De Beer recalled that Tambo had said that “large sectors of the economy would be left open to private enterprise.” (Guardian Weekly 5 October 1985) In an interview with Anthony Heard, Cape Times editor, Oliver Tambo said that “Everyone’s property will be secure.” By 1987 the South African Financial Mail, reporting on the Dakar, Senegal talks, reported that the ANC delegation “had agreed that there was a distinction between ownership of minerals, which belonged to the nation, and the right to extract it which must be purchased. This section might have to be reworded, an ANC representative said.” (14th August, 1987)

Comrade Ronnie Kasrils in an otherwise courageous and commendably honest acknowledgment of the betrayals in the negotiations in the preface to the latest edition of his biography, Armed and Dangerous attributes what happened to the naivety of the leadership in the Codesa negotiations. This is a mistaken view. The foundations of the Codesa betrayals were embedded in the SACP’s theoretical DNA and the class character of the ANC. The SACP’s 1962 programme spells this out very clearly:

“The immediate and imperative interests of all sections of the South African people demand the carrying out of… a national democratic revolution which will overthrow the colonial state of White supremacy and establish an independent state of National Democracy in South Africa. The main content of this revolution is the national liberation of the African people.

“It is in this situation that the Communist party advances its immediate proposals before the workers and democratic people of South Africa. They are not proposals for a socialist state. They are proposals for a national democratic state.” (emphasis added)

Although SACP general secretary Joe Slovo was to recognise the inextricable link between the struggle for national liberation and the overthrow of capitalism in his “No Middle Road”, it was the same Slovo, in an address to the board of Woolworths in the early 1990s who argued that “nationalisation would be extremely costly… [would] be met by capital flight and skilled manpower and possibly lead to economic collapse. He likened nationalisation to “’consigning the height of our economy to a commandist bureaucracy’” (WWM, 60 Years of the Freedom Charter)

The ANC on the other hand was never a workers party, but a party of the black middle class and the aspirant black capitalist class. The leadership repeatedly made it clear that it never stood for socialism from Mandela in 1956 to Thabo Mbeki whose address to the 1998 Cosatu congress was but one example. After the adoption of gear Thabo Mbeki went so far as to say “Call me a Thatcherite”. The ANC’s commitment to capitalism was complemented by the SACP’s championing of the two-stage theory on which the concept of the National Democratic Revolution is based. In combination they provided the political basis for the betrayals consummated at Codesa.

Total capitulation followed rapidly after the initial “re-interpretations” of the Charter. The Charter was abandoned even before the 1994 elections and substituted with the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) stripped of the nationalisation notions so offensive to the capitalists. If the ANC was on its knees at Codesa, by 1996, barely two years into democracy, it was on its belly licking the boots of white monopoly capital and imperialism after jettisoning the RDP and adopting the neo-liberal GEAR programme.

Despite the fact that the outcome of the deliberations at the Congress of the People had been manipulated to dilute the Freedom Charter, denuding it as much as possible of the revolutionary socialist aspirations of the worker delegates, the mobilisation for the Congress was much more democratic and based on inviting workers and activists contribute towards its contents and to debate them at the event itself. In sharp contrast GEAR was developed by a team of experts from the World Bank and selected ANC leaders trained in the ideas of the Washington consensus. It was adopted by cabinet without even the ANC NEC being consulted and presented to the ANC conference in Mafikeng a year later as an accomplished fact merely for rubber stamping.